Published Writings

"Farewell to a Saudi animal rights activist", Qantara.de, 25 Sept 2020.

In late August, Twitter was awash with grief and disbelief at the gut-wrenching news of the passing of a man known only by the pseudonym Barg ou Ra'd ("Lightning & Thunder"). Reem Kelani says farewell to a popular Saudi animal rights activist whose identity was revealed only after his passing.

Click here to read Reem's article.

"Whoever dares say anything against Saddam.....", al-Qabas, 13 Aug 2019.

Reem Kelani looks back at the Iraqi invasion in Aug 1990 and its ramifications.

Click here to read Reem's article in Arabic.

"Between Orientalism, Normalisation and Cultural Appropriation", Whispering Dialogues, May 2019.

Reem explores Israeli cultural appropriation, not just of food and costume, but also of secular songs from Yemen.

Click here to read Reem's article in Arabic.

"Farewell to the film-maker Axel Salvatori-Sinz: producer of Les Chebabs de Yarmouk", Romman, 8 Feb 2018.

Click here to read Reem's article in Arabic.

Obituary: "Actor Abdulhussain Abdulredha: The fourth tower of Kuwait", Qantara, 25 August 2017.

Click here to read the obit Reem wrote in English for a non-Arab audience.

And click here to read the obit Reem wrote in Arabic for Arab readers.

The collective traditional song versus the individual original tune: the example of the American Songster, Rumman magazine, 2017.

Flemons "focuses on the undocumented stories of African music in America as well as on re-claiming the historical and political context of ‘minstrel’ and ‘black cowboy’ songs. The minstrel artist in American history was, in the main, a white singer who would black up in order to sing songs of African origin which, in essence, had nothing to do with him".

Click here to read the original article in Arabic.

And click here to read the article translated into English.

Being Palestinian: Personal Reflections on Palestinian Identity in the Diaspora, Edinburgh University Press, 2016.

"I am Palestinian because I sing traditional songs" - from Reem's contribution to this collection of personal accounts of what it means to be Palestinian.

Reem Kelani: "Mohammed Assaf: champion of the people or the powerful?", Electronic Intifada, 29 July 2013.

Click here to read Reem's article.

"Confronting the International Patriarchy: Iran, Iraq and the United States of America", edited by Philippa Winkler, published by Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2013.

Winkler: But nothing can crush the spirit of women as they challenge local patriarchies. This is illustrated in Chapter Four, the elegant essay offered by Reem Kelani, Palestinian singer, musicologist and broadcaster. Born in Manchester and brought up in Kuwait, Kelani describes in “Write it down... Artist or prostitute: perspectives on female creativity and activism in the Arab world”, the ways in which the experiences of women Arab singers, including her own, sit at the intersection of activism, resistance, creativity and music.

Reem Kelani: "The Israel Boycott", Songlines magazine, July 2012.

Click here to read Reem's argument in favour of a cultural boycott of Israel

Reem Kelani: "Sayyid Darwish: music to Palestinian ears", Journal of Palestinian Refugee Studies, Spring 2012.

In her essay, Reem explains the relevance of the late Egyptian composer Sayyid Darwish to Palestinians (See Pp 15-17).

"Reem Kelani: Notes from Tahrir Square", Opera North, Leeds, 21 March 2012.

Click here to read Reem's article.

"The Neo-McCarthyism of the London Philharmonic Orchestra", al-Akhbar, Lebanon, Wednesday, 21 September 2011.

Click here to read Reem's article (in Arabic).

"On Art and Normalisation", al-Akhbar, Lebanon, Friday, 16 September, 2011.

Click here to read Reem's article (in Arabic).

Driving UK Research (Is Copyright a help or a hindrance? A perspective from the research community). Reem contributes with her own take on copyright law, July 2010.

Singer, musician, broadcaster and educator Reem Kelani writes about her experiences with researching Arabic music and bringing it to a wider audience. She describes the difficulties copyright law creates in accessing sound and video recordings for researchers, particularly those not permanently attached to educational establishments.

Prior to the completion of my first major project four years ago, I spent some 20 years researching Palestinian songs through interviews with older women in refugee camps, in the Galilee and in the Diaspora.

Along the way, I gave workshops in schools and for community choirs in the UK and internationally. My work overseas included working with elementary school children in Greece, conducting workshops for Syrian children at Solhi al-Wadi Institute in Damascus and singing to children in Seattle. The key components of my workshops are to teach the basics of Arabic music and to introduce audiences to Palestinian culture.

Over the past year, the Rare Books & Music Reading Room at the British Library has become my second home. When I originally embarked in 2003 on my current project researching the music and life of Egyptian composer Sayyid Darwish (1892-1923), I didn't think for a moment that I would be still working on it almost seven years on.

Darwish lived at a pivotal time in Egypt: at the end of Ottoman rule, during British colonial rule and at the birth of Egyptian nationalism, events that would change the course of Arabic music forever. Hence, and in my quest to understand more fully Darwish's musical and cultural genius, I find myself asking the staff at the British Library Sound Archive Listening Service for recordings ranging from early twentieth century Egyptian music, classical Turkish music, sacred Muslim and Eastern Christian chant, Italian opera, WW1 songs and even Jazz from that period.

But that's where the good news ends. When I was in Istanbul recently, I was trying to find a specific rare recording to play to Mehmet Güntekin, Director of Classical Turkish Music for Istanbul 2010. YouTube is banned in Turkey, as I learned to my surprise, and thus I found myself unable to play the recording from the web. I was mortified at this lost opportunity to share and discuss this piece with an expert on a trip on which I had embarked at my own expense and for my own research.

It is an anomaly that whilst I can make photocopies of excerpts from the many books about Sayyid Darwish at the British Library, copyright law doesn't allow me to borrow copy or 'rip' any audio or audiovisual recordings. And I am certainly in no position to become a collector of rare recordings, even if they were available for sale. I have neither the money nor the space for that.

I am able to find so many interesting recordings online, but for an independent freelance researcher with no affiliation to an academic or cultural body, this is neither a permanent nor a reliable source. Moreover, few of the recordings online have any accompanying notes, and even if they do, their accuracy is an open question.

I would like to see an extension of the principle of 'fair dealing' to sound recordings and film, knowing full well that this would apply both ways, and that if an independent researcher wished to access my published recordings in this way, I neither would nor could have any objections.

On the contrary, honest and open exchange between researchers is not only desirable but essential for the very success of all our endeavours.

Read the British Library's publication in full.

Burj el-Barajneh Dispatch, Middle East Report, Spring 1999

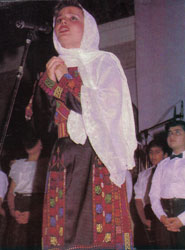

After making my way through the rubble and squalor of the overcrowded refugee camp near Beirut's International Airport, I arrived half an hour late for my appointment with Umm Muhammad, a local living repository of Palestinian folk song traditions.

Umm Muhammad, or as she pronounced her name in the northern Palestinian dialect, "Im Imhimmad," warmly welcomed me into her spotless, tiny apartment. It was 'Id al-Fitr (the feast concluding Ramadan), and the air was spiced with the scents of Arabic coffee and freshly baked date cakes. Umm Muhammad led me into a cozy room, where we began our interview. At first I had trouble hearing her over the squawking of a television blaring Arabic "video clip" pop songs, dubbed Mexican soap operas and annoying foreign advertisements.

Umm Muhammad looked askance at my tape recorder as she began recounting Palestinian musical traditions. When I asked her to sing a song from Palestine, the floodgates opened. "I want to sing you some 'ataaba," she said. 'Ataaba is a form of improvised colloquial sung poetry that has existed for centuries in Greater Syria and Mesopotamia. "Which theme of 'ataaba would you like to sing, mother?" I asked. "Furaqiyyaat, my girl." She referred to a genre of songs that convey nostalgia and sorrow over the loss of loved ones.

Umm Muhammad's voice was very strong for a woman in her late seventies; it expressed a depth of passion that no formal music training could have provided. The earnest huskiness of her voice brought to life the land and the people about which she sang. Clearly, I was in the presence of a fine exponent of musical tradition.

During intermissions between songs, Umm Muhammad discussed politics openly. "They sold us for pennies," she complained, referring to Palestinian and Arab leaders. When I asked her to be careful of what she said on tape, for her safety, she defiantly retorted: "'Ala teezi [my ass]! Let them kill me if they wish! I fear no one!"

When questioned about the fate of the Palestinian refugees in Lebanon, Umm Muhammad's answer conveyed a deep and bitter weariness. "No one wants to know. They might as well put us all in one huge container and get rid of us with one shove, instead of this slow death." The "container" analogy brought to mind horrific images of European Jews during the 1930s and 1940s. No sooner had I thought this, than she beat me to it by adding, "I lost my husband and a son in two wars. Why did they make us pay the price for World War II?"

She showed no self-pity, however, only surprise and puzzlement. She was ready to forget the misery of the 350,000 or so Palestinian refugees in Lebanon for the sake of one stone-throwing youth in the West Bank. "Forget about the Palestinians here in Lebanon; our fate was sealed long ago. But I watch these brave young men on television and I pray for them."

I asked Umm Muhammad about the "right of return," and she told me that she had actually "returned" once to her birthplace, Acre ('Akka, in Arabic). "I went back to 'Akka two years ago," she recounted. "A relative of mine got a permit for me to visit. Would you believe it?! I needed a permit to visit my own homeland!" Curious, yet apprehensive, I asked her how she found it. Umm Muhammad's eyes sparked. "I left my cousins young, and now they are old. Women my age use crutches over there, not like your Umm Muhammad here! I even managed to do the sword dance at a wedding in 'Akka!"

"Did you kill anyone with your sword?" I inquired cheekily. "Kill anyone? Of course not! The dancing area in the village was so big, I couldn't have reached anyone with my sword even if I'd wanted to. I danced to a famous song." I asked what song and she grabbed the tape recorder and launched into a well-known song style that accompanies a traditional dance called sahjeh. This dance features two lines of men standing opposite each other (called sahhaajeh), clapping their tilted hands in unison towards the floor. Sometimes, a woman, or a group of women, dances between the lines of men, holding a sword or a dagger. The main song is usually performed by at least one lead singer (Hadda' or Hadi). The rest of the participants act as chorus, singing a refrain: "Ya halali ya mali…. Ya halali ha mali," meaning "what I have is mine by right."

As I said goodbye to Umm Muhammad and her family, the call to afternoon prayer (adhaan) wafted over the confined space of the camp, blending harmoniously in my ears with the last, stirring verse that Umm Muhammad had sung. It made me realize that we Palestinians had indeed once lived on our land. I also realized, as I left the entrance of the dismal camp, that we had not safeguarded that land, that halal.

People like Umm Muhammad make me believe in the possibility of regaining our halal.

"Ya halali ya mali… Ya halali ya mali…"